Three Lives of a Woman in Traditional Kalmyk Culture

Among the nomadic Oirat-Kalmyks, who practice Buddhism, a woman's social status was linked to her age, from times of yore.

Among the nomadic Oirat-Kalmyks, who practice Buddhism, a woman's social status was linked to her age, from times of yore. Three cycles stand out clearly in a woman's life: the first is as a young girl in her immediate family; the second is as a married woman in her husband's family; and the third is as the matriarch of the entire bloodline.

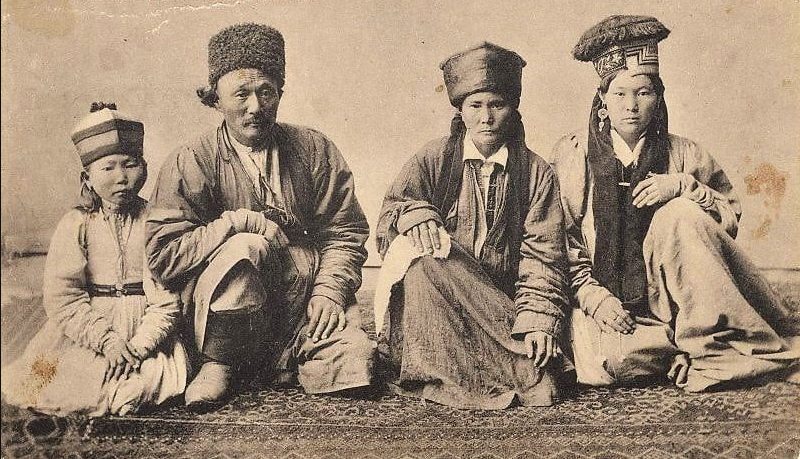

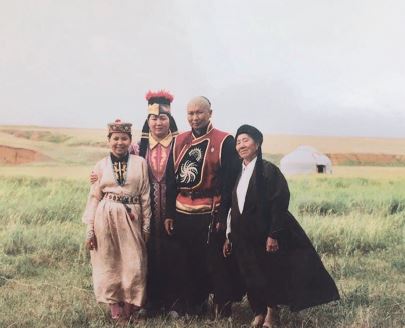

Transitioning from one cycle to another would be signified by a change of her traditional clothing and headwear. There are three types of traditional female outfits still known to play a symbolic role amongst the Oirat-Kalmyks: that of an unmarried girl’s, a married woman’s and an elderly grandmother’s.

According to the Oirats’ traditional beliefs: a girl was considered a pure being, a temporary guest in her parents' house. Girls were typically given away in marriage early - at the age of twelve to fourteen. Therefore, they were considered a guest in their parents' house who would soon depart their immediate relatives forever. This premise determines the whole attitude towards the daughter. Girls were not burdened with heavy work and were more engaged in sewing and embroidery, etc. If possible, parents would pamper and dress them in more ornate and luxurious clothing. The girls had to braid their hair into one braid and wear it slung onto their backs and wear one earring in their right ear. The color of the fabric for girls' dresses was chosen in light shades of blue or green, where possible. If the fabric was patterned, it would be simple and not too bright. The girl, as a heavenly pure being, is not to excite the senses with various shapes and colors. That is, spirituality and purity were emphasized in every possible way.

When a girl got married, according to Kalmyk tradition, there would be a radical change of status. She essentially stops being a member of her immediate family and becomes a member of the husband’s family. So, when a bride is taken out of her parents’ home, they are obliged to perform the ritual "daalkh avlhon (taking the life force)", which similarly occurs when a deceased member is carried out of the home so that "happiness, the life force of the family" does not evaporate with the newly departed girl. Then, arriving at her in-laws home, she is given a new name, redressed as a married woman and her maiden jewelry is replaced with two earrings. At the wedding, a special ritual also takes place which involves splitting the single braid into two.

A married woman's costume was very ornate, often embroidered with gold and silver. The color for the dress (terlik) and the cape (tsegdg) would have bright colors, the most popular being various shades of red. Red represents the color of blood, love and life and is meant to emphasize the main function of a married woman - the giving of new life. The status of a married woman was associated with many restrictions on her behavior with her husband's relatives as well as with strangers and/or guests. For example, she would not be allowed to approach the Buddhist altar in her own yurt or sit on the male side of the room where that was considered a place for honored guests and elder relatives to sit. These restrictions reflect the protracted process of inclusion of "strangers" into the circle of blood relatives, as well as measures to prevent extramarital relationships.

A third transformation takes place when a Kalmyk woman completes her childbearing years and becomes a grandmother. Elderly women were obliged to wear an outfit, that essentially resembles a man's outfit. The headwear was made of black or gray karakul with a red tassel. The dress-berz, devoid of embroidered ornaments, was the same as a man's beshmet, only worn long down to the ankles and sewn from dark blue or dark brown single-tone fabric. Earrings would be made of silver, but without a gemstone . The elderly woman would be held in high regard and with a privileged status. Like elderly men, she is seated in a place of honor during visits by others, she smokes her pipe and her advice is listened to. There are also cases when an elderly mother becomes the ruler of an entire clan. I believe that this acknowledges the woman's merits as the founder of the family and because her blood runs in the veins of all her children and grandchildren, she is finally accepted into the circle of the relatives.